Originally posted February 5, 2009

“Good design for us means as little design as possible. Not for reasons of economy or convenience. It is surely one of the most difficult tasks to arrive at a really convincing, harmonious form by employing simple means…More complicated, unnecessary forms are nothing more than designers’ escapades, which have the function of self-expression instead of expressing product functions…The economy of Braun design is a rejection of this type of design; it leaves away everything superfluous to emphasize that which is more important.”

Few design companies have enjoyed the amount of critical and commercial success that Braun has for the past half century. Founded in 1921 by the engineer Max Braun, the company vaulted to prominence when his sons Artur and Erwin took the helm in 1951. Artur Braun, in particular, recognized the market potential for progressive design thinking in the burgeoning post-war field of consumer electronics. Part entrepreneur, part design auter, Artur turned to the fledgling Ulm School and its rationalist design principles for input. He hired Dieter Rams in 1954, and surrounded him with other Ulm alumni, including Hans Gugelot, Fritz Eichler, Gerd Muller, and Weinhold Reiss. The collaboration proved fruitful, and the Braun product line expanded from radios and hi-fi equipment to electric shavers, fans, hair-dryers, blenders, and televisions. By the end of the 1950’s, Braun had become the avatar of a fresh and clean-looking visual aesthetic that helped transform the design landscape.

The driving force behind Braun design was Dieter Rams. Rams was officially appointed design director in 1962, and he remained in this position until he retired in 1995. Rams’ design philosophy was, literally, simple, and was described by his colleague Rudolf Schonwandt as “order rather than confusion, quiet rather than loud, unobtrusive rather than exciting, sparse rather than profuse, and well-balanced rather than exalted.” In his own writing and speeches, Rams indicated strong opposition to extreme visual stimuli and stylistic obsolescence. He abhorred the chaos he perceived in the visual environment, a chaos stemming from too many designs that called attention to themselves, and too much turnover for mere novelty. Rams attempted to counter this with designs that “integrate better and more pleasantly into people’s surroundings.” Long usage would make these products even more familiar and comfortable.

Rams did not turn a blind eye to appearance, but he sought a timeless rather than a modish beauty, and clearly favored a minimalist visual aesthetic. His mantra of “less, but better” was not a devaluation of the role of design, but rather a reassessment. As the quote at the top suggests, the design process at Braun was intensive and meticulous, concerned with proportions to the last millimeter, and with details to the last screw fastener.

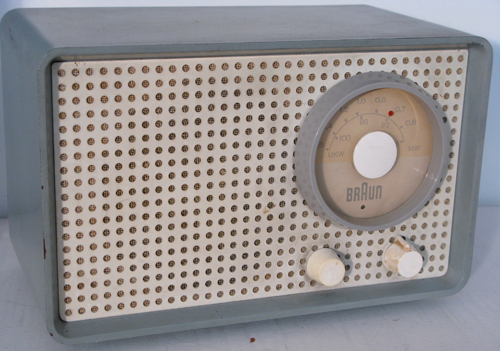

Two products, both illustrated here, exemplify the sea-change in design that took place in the mid-century: the SK-2 radio of 1955 and the SK-4 phono/radio of 1956, also known as “Snow-white’s coffin.” The SK-2, designed by Artur Braun and Fritz Eichler, is to my eye one of the most beautiful and abiding examples of product design from the 20th century. Transistor technology permitted a reduction in scale and the metal case permitted a reduction in material to a maximum thinness. The simple but brilliant decision to extend the speaker perforations across the entire face turned a functional element into a unifying graphic element, one that moreover expresses the underlying aural nature of the product.

Function is self-explanatory, organized logically and legibly into on/off, volume, and station. The SK-4, designed by Dieter Rams and Hans Gugelot, similarly exposes and conveys its function, showing operating elements without disguise or ornamentation. The plastic cover literally conveyed transparency, and quickly became industry-standard.

The run at Braun under Rams’ stewardship was remarkable for its continuity and consistency. If evidence of the excellence of Braun’s product designs is needed, it can be gleaned from length of the production runs of Braun products, how long these products hold up in usage, the number of Braun designs in the permanent design collections of museums such as MoMA, and the demand for vintage Braun designs among design collectors today.

Images from top: Electric shavers, SM-3. Gerd Muller, 1960. Photo from Flickr; Photonium. Record player PS 45. Dieter Rams, 1962. Photo from Flickr; Photonium. Pocket radio T-41. Dieter Rams, 1959. Photo from Flickr; Marcos Dupico. SK-2 radio. Artur Braun and Fritz Eichler, 1955. Photo by LPW 2. SK-4 phono-super. Dieter Rams and Hans Gugelot, 1956. Photo from Flickr.