Originally posted February 10, 2011 on interiordesign.net

Many mid-century surveys of decorative and industrial arts have an agenda of celebrating and promoting the work of a nation, region, or city. So it is refreshing to come across one that finds industrial production wanting, and posits room for improvement. And you have to like a picture book that begins with a chapter entitled “Craftsmanship and Cybernetics.”

“Modern Design in the Home,” by Milena Lamarova, is the book in question. Published in 1965, it surveys postwar Czech design in furniture, glass, ceramics, and textiles. Glass and textiles had particularly rich and deep traditions in the region. But beyond her national design heritage, the author is absorbed by the Big Questions in modernist aesthetic theory. Like, regarding domestic objects such as bed, bowl, and cup, with prototypes in antiquity, “should (we) take national culture into consideration or simply throw out the old traditions,” and “Should (we) look for totally new forms and shapes or should (we) adapt and develop the traditional ones?” Behind these questions is a reckoning of the role of craft in the machine age.

It is precisely in the domestic arena that battle lines between old and new are drawn, literally hitting home. As Lamorova notes, “we look to [familiar and constantly used objects] for the physical assurance that there exists an organic connection between the world of man, the world of things and the world of production.” If these things disappoint, we become disoriented and disturbed.

Ultimately, Lamorova speaks for an extension of mechanical production in service of human needs, including the need for diversity. She sums up thus: “The value and beauty of an object should be related to the force and depth of thought which gives birth to it. There is no reason why it should not be produced by the machine. This is nothing more ore less than an attempt to give a deeper meaning to our modern technological civilization.”

The themes developed in the first, discursive chapters continue through the book. They echo what was going on in progressive design circles in America and Western Europe with the following key difference: in 1948, all Czech industries were nationalized, and in 1959, an umbrella organization responsible for glassware, ceramics, plastics, fabrics, clothing, and furniture was created, called the Institute of Home and Fashion Design. So what developed in the private sector in the West was essentially governed in the command economy of Czecholsovakia, with mixed results.

A cross-section of Czech production design, as presented here, confirms at least one supposition as to why mid-century Czech design is not better-known in the West: much of it is derivative of Danish and American design, and of average visual quality. Still, there are notable exceptions, particularly in the areas of glass—an unbroken eight century tradition in Bohemia—and textiles. Six examples across the board, follow:

A sideboard in natural and laquered ash with metal legs, designed by Frantisek Jirak, and produced in 1963. Also in this shot is a hand-knotted rug by Jiri Mrazek.

Metal-frame chairs by Otto Rothmayer, produced 1960-63.

Blown glass jars with lids. Designed by Vratislav Sotola and produced at the Borske works, 1963.

Decorative bottles in opaline and colored glass, by Josef Hosopdka, also for Borske, 1963.

Tapestry-style woven fabric in cotton. Designed by Vera Drnkova-Zarecka, and produced by Umelecka remesla, Prague, 1963.

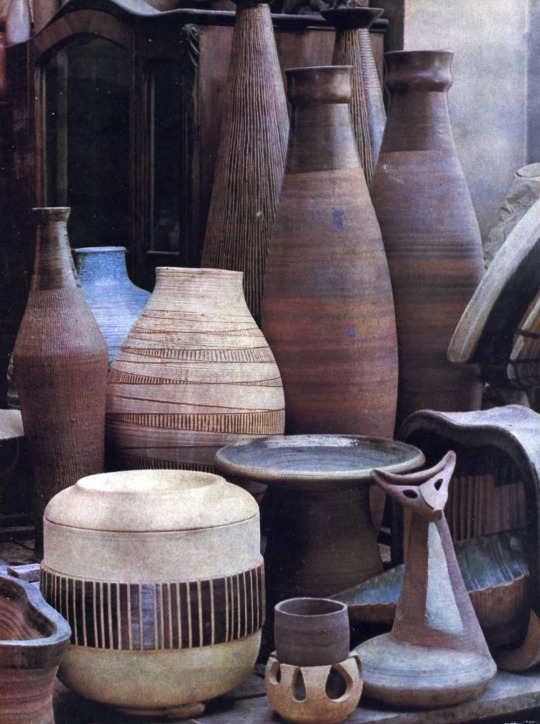

Group of vases in coarse clay by Julie Horova-Kovacikova.