Originally posted January 28, 2010 on interiordesign.net

Dona Meilach (1926-2008) was a seemingly indefatigable connoisseur, champion, and chronicler of craftsmanship. All told, she wrote over 40 books and several hundred articles on a broad range of craft topics and techniques. A glimpse at some of the titles—“Creating Art from Fibers and Fabrics,” “Creating With Plaster,” “Papercraft,” “Collage and Assemblage,”—speaks to the encyclopedic breadth of her interests, as well as the depth of her knowledge: she not only studied but also performed the crafts she wrote about.

Her tactile, scholarly, and catholic approach enabled her to deeply understand the craft movements of her era (1960-80’s), and to grasp the tendencies and elements that were significant and innovative. In my library, I have three of Meilach’s books: “Contemporary Art With Wood” (1968); “Creating Modern Furniture” (1975); and “Woodworking, the New Wave”(1981). Along with “Creating Small Wood Objects as Functional Sculpture” (1976), these works form as good an introduction to postwar craft woodworking as exists. Part how-to guides, part visual encyclopedia, these books provide both detailed technical information and lavishly illustrated curatorial information.

“Creating Modern Furniture” is the focus of the present post. Subtitled “Trends, Techniques, Appreciation,” it provides an overview of the craft woodworking movement of the mid-70’s, featuring 580 photographs, mostly of works by a multitude of American artisans. The first part of the book describes woodworking techniques and praxis, including sawing, sanding, grinding, joining, gluing, finishing, and veneering. Trees, wood, lumber, tools, and even work area and safety are discussed.

As interesting as this is, the book’s value lies in the examples that are shown—Meilach had a truly great eye for innovation and beauty. With hindsight, the book contains work by the usual suspects, who may or may not have been usual suspects at the time.

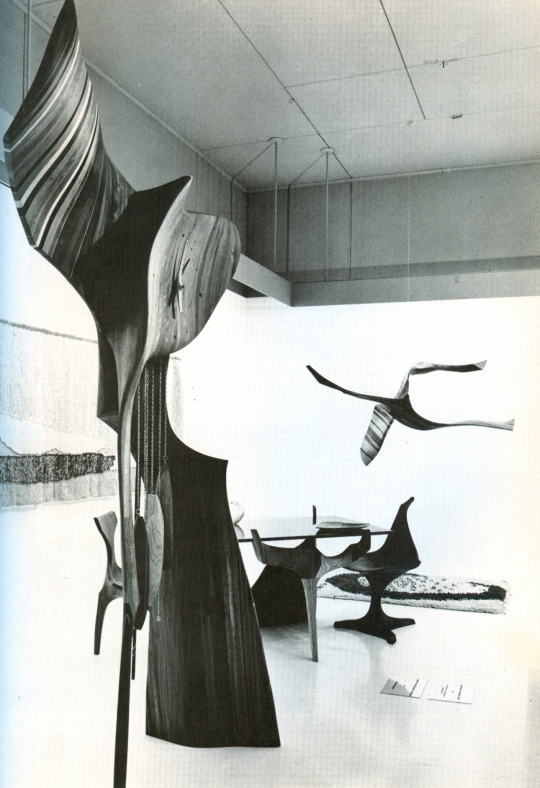

This list includes Michael Coffey, Gary Knox Bennett, Jack Rogers Hopkins, J.B. Blunk, Wendell Castle, Mabel Hutchinson, Jere Osgood, George Nakashima, Wharton Esherick, and John Makepeace. The standout here for me is Jack Rogers Hopkins, a California artisan who worked in laminated, steam-bent woods. I’ve included an image of an installation with a grandfather’s clock and a dining table, and a close-up of the dining table, which to me is the most stunning object in the book. Meilach cites Hopkins for virtuosity, and notes that the interaction of the various wood colors in the table (teak, maple, and birch are used) adds to the total sculptural concept.

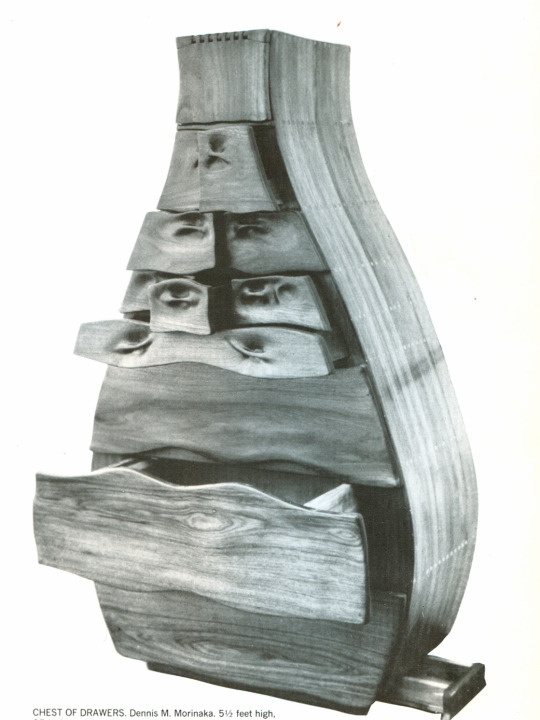

Beyond the dozen or so artisans who have become household names in the design market, there are a few dozen more with similar talent, and here the book becomes a guide to future collectability. A few of the more eye-popping works, shown here, include a low table of African Padouk wood by Joe Barano (“a marvelous interplay of sculptural forms”); a coat tree and lounge chair by Edward Livingston; a double love seat of fir by Robert Dice; a “Clam” chair of walnut with fur and leather interior by Edward Jajosky that closes on itself; and a door by sculptor and jewelry designer Svetovar Radakovitch that includes surprises such as inset chunks of colored glass and cast bronze hinges. As striking as these pieces are, they do not even figure in the chapter “Fantasy Furniture,” which includes a surreal-looking chest of drawers in a mélange of woods by Denis Morinaka and a cabinet with doors-within-doors by Ann Maimlund, both pictured here.