Originally posted August 12, 2010 on interiordesign.net

There is considerable reason to think Mexican modernist design will gain traction in the American market. Simple proximity to the United States, an indigenous tradition of craftsmanship, exotic materials, an expatriate community of designers, Marxist politics, and wealthy local patrons all point to a period of creative combustion ready to be rediscovered by market makers ever-hungry for new material. A 2006 monograph on Clara Porset, a 2007 museum show in Mexico City accompanied by a 566 page catalog entitled “Vida y Diseno en Mexico en Siglo XX,” and a recent monograph about Pedro Friedeberg, have raised awareness and piqued curiosity, while providing the basic scholarship that helps fuel sales.

Looking through “Vida y Diseno” it is easy to understand the appeal of Mexican modernism. Much of this well-edited and lavishly produced book is eye candy. The pieces in it appear familiar but with a twist; the sensation is like seeing undiscovered works by Gio Ponti or Charlotte Perriand. Mid-century standouts include a wood and tubular steel chair by Bauhaus-trained Mathias Goeritz, a decorative tiled table by Juan Cruz Reyes, a solid and naturalistic coffee table by Don Shoemaker, an “Equipal” chair by Pedro Ramirez Vasquez, and any number of works by Arturo Pani, Michael Van Buren, Clara Porset, or Pedro Friedeberg. Notable recent works include the sustainable furniture of Emiliano Goyod and Hector Galvan. The book reads like a who’s who, and figures to become the standard reference (and buyer’s) guide to Mexican modernist furniture.

Not included in “Vida y Diseno” is the work of Charles Allen and Edmund Spence. This is because both are American, and neither lived in Mexico. Spence made a career out of translating international modern styles for the U.S. market–he designed a successful blonde wood line made in Sweden and imported by Walpole Furniture of Massachusetts. Spence’s Mexican venture, dubbed the “Continental-American Collection,” was launched by Industria Meublera in 1953. A contemporary ad boasts “superb raw materials [and] fine Mexican handcraftsmanship,” and shows an Aztec stone deity apparently putting his imprimatur on three chair designs.

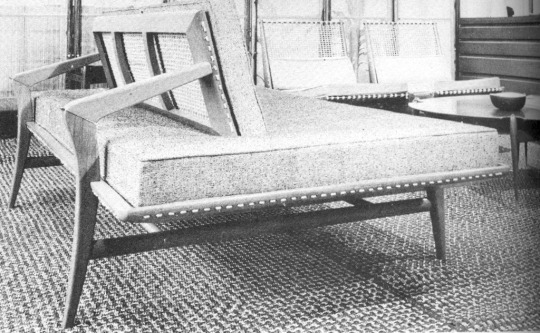

Somewhat less commercial, and more elegant and sophisticated, is Charles Allen’s line for Regil de Yucatan, imported by Yucatan Crafts–think Robsjohn-Gibbings does Tulum. An interior designer and muralist turned furniture designer, Allen was an aficion of the native woods and natural finishes found in Yucatan. His rakish, saber legged chairs and daybeds were hand crafted of solid mahogany, and woven with local sisal, while his case pieces incorporated machiche, grenadilla, and bajon woods in addition to the brass rods holding together the distinctive saw-horse bases. All finishes were hand-rubbed. In describing the collection in a 1952 article, design writer Gladys Miller enthused that it “fits perfectly when placed in the contemporary, casual but orderly and disciplined home.” Maybe Allen really did do his homework–the Mayans were nothing if not orderly.

Arguably, both Allen and Spence are susceptible to charges of cultural imperialism for appropriating stylistic elements and utilizing cheap labor and cheap, even endangered materials. Still, in terms of recognizing the design potential in Mexico’s cultural mix, and introducing Mexican-made modern furniture into the American market, Allen and Spence were well in the vanguard of a growing movement. As the market for Mexican modernism develops, look for blue-chip status to be conferred on certain designers, as with Brazilian design in the past decade. Look for the top galleries and auction houses to continue to offer up these names, and to dig deeper into the Mexican modern heritage. And look for Charles Allen’s mid-century designs at your local thrift shop, before these too are scooped up.