Originally posted December 11, 2008 on interiordesign.net

My first exposure to the photography of Wingate Paine occurred about 10 years ago when a portfolio of his work turned up in a gallery on Lafayette Street in Manhattan. As I sifted through hundreds of unframed images, I learned that the then-obscure Paine had been a leading fashion and advertising photographer in the early 1960’s who quit that scene to do a homage to womanhood. The work I was looking at was erotically charged and cinematic: think Mad Men meets Blow-Up.

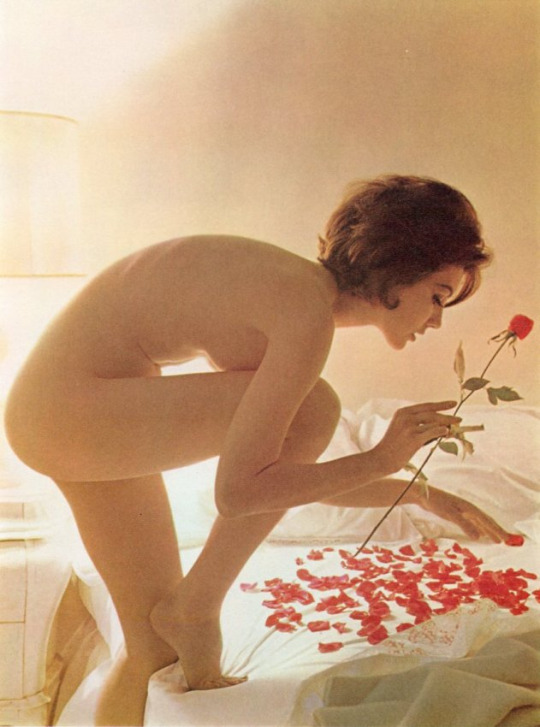

What caught my attention was the mood—the images channeled Mary Quant’s London, though Paine was as American as Ansel Adams. Of course, it didn’t hurt that the women were stunningly beautiful, and often more naked than not.

Paine himself had an unusual and varied career trajectory. Born in 1915 into a Boston Brahmin family—namesake of a Founding Father—he eschewed his hereditary connections in banking and law to become first a Marine captain, then by turns a yoga devotee, wine connoisseur, photographer, filmmaker, and later a sculptor and Buddhist teacher and writer. After a long period of neglect, Paine’s stock has been rising in recent years. His work has been turning up at auctions such as Swann’s, Wright, and Rago, and has been shown in galleries in New York and Los Angeles. Tonight, the first solo exhibition of his photographs opens at the Steven Kasher Gallery in New York City. Running through January 17, the show features over 75 vintage prints from Paine’s personal archive, drawn primarily from his 1966 book Mirror of Venus. Co-written by Francoise Sagan and Federico Fellini, Mirror of Venus has been reprinted 10 times in four languages. Paine’s photographs of three models/muses provide vicarious pleasures, if not titillation. Tame by today’s standards, the book pushed boundaries in its day. Though tinged for us with 60’s nostalgia, the images remain visually fresh, if only because the decade keeps cycling back into fashion. The text, unfortunately, seems dated to our post-feminist sensibilities.

Witness Francoise Sagan: “For a woman the time/is often the time./After the time,/it is sometimes the time;/but before the time, it is never the time.” I know I don’t understand women; I certainly don’t understand Francoise Sagan. At least Fellini is more straightforward: “Why can’t we always live in a house full of women like this(?)” Why indeed. For an experience that is highly evocative and a bit provocative, try the book, or better yet, see the exhibition.