Originally posted Septermber 3, 2009 on interiordesign.net

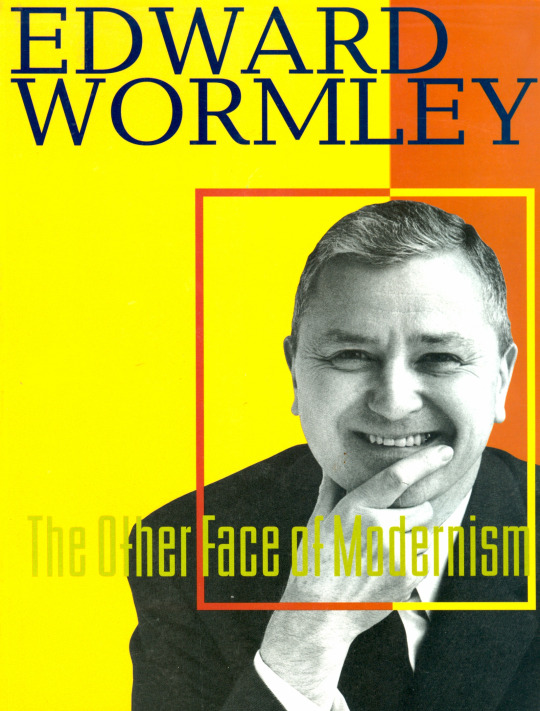

I’m finding it hard to believe it’s been 12 years since Lin-Weinberg presented its groundbreaking Wormley exhibition, and published the accompanying catalog, “Edward Wormley: The Other Face of Modernism.” While we could not take credit for discovering Wormley—he had remained on the radar, though his fortunes had slipped—we did help nudge him back toward the center of the modern design map.

Four years later, in the aftermath of 9/11, we revisited Wormley with an installation at Sanford Smith’s Modernism + Art20 show. Here, we attempted to create an interior that would merit Wormley’s approval. The work helped us put one foot in front of another through a very difficult period, and the results seemed to be appreciated by a shell-shocked design community. Here is what I wrote at the time:

“It has been four years since Lin-Weinberg presented [its] retrospective exhibition [on Wormley]. In this period, there has been a resurgence of interest in Wormley’s furniture designs, from icons such as the ‘Listen-to-Me’ chaise to unassuming side tables and benches. And this is justly so. Wormley possessed a keen eye for style and proportion, an ability to work both with fine materials and industrial techniques, and a commitment to comfort and flexibility. His best designs rank with the best designs of the period, either for usefulness and economic value, or for sheer exuberance and imagination.

Yet, Wormley’s rediscovered stature as a furniture designer should not obscure his talent and significance as an interior designer. From 1944 on, Wormley kept an office in New York City from which he took on residential commission work. He also designed the interiors for Dunbar showrooms, installations, and catalog layouts. Critics praised Dunbar showrooms for their aplomb and virtuosity, for adaptability, unerring taste, and sound, unpretentious good sense. A Wormley interior incorporated a broad range of influences, ranging freely across geography and time, drawing inspiration from East and West, past and present. Finishing touches included Moroccan rugs, modern paintings, and African sculpture. Wormley once called himself a middle ground designer, and indeed his work occupies an interior middle landscape, mediating between the agenda of the International Style and the often competing claims of tradition and craftsmanship. Wormley’s brand of modernism allowed for familiarity, memory, and personality. His interiors were templates for self-expression, balancing accent pieces for drama and excitement with an underlying architectural sensibility that favored clean lines and simple elegance.

More than as a designer of individual pieces of furniture, Wormley should be remembered for the living spaces he created. As an interior designer, Wormley anticipated a multitude of needs and built interiors “for the comfort, dignity, and sense of security of human beings.” (John Anderson, Playboy, 1961) Wormley’s aesthetic vision reached its fullest expression in his interiors. His was an art of assemblage, of juxtaposition and composition, whether of elements within a piece or of pieces within a setting. Our installation seeks to showcase Wormley’s ability to blend old and new, luxurious and simple, into a practical, harmonious, and dynamic modernist interior.”

Today, Wormley is recognized as the modern American master he was. His pieces sell at top galleries and auction houses, and are placed into projects by leading interior designers. Dunbar has even been revived, and is reproducing some of Wormley’s designs. Last year, Todd Merrill included a chapter on Wormley in his survey of American studio furniture, “Modern Americana: Studio Furniture from High Craft to High Glam.” And few people are asking, as they were at the exhibition opening in 1997, “Who is Wormley?”