Originally posted May 6, 2010 on interiordesign.net

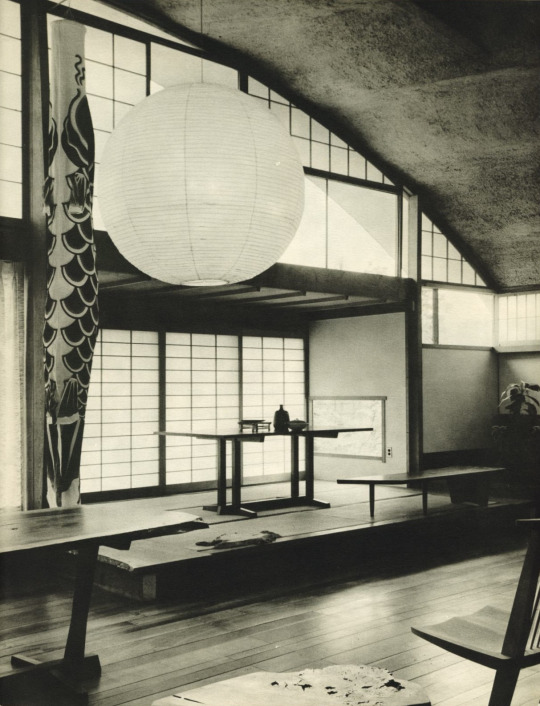

“Furniture, we feel, is a development of mood besides being purely utilitarian. Basic forms with the reflection of the constancy of nature find satisfaction in times like ours. A small poetic haven in an unsettled world where excitement seems so necessary.”

George Nakashima, from his 1962 catalog

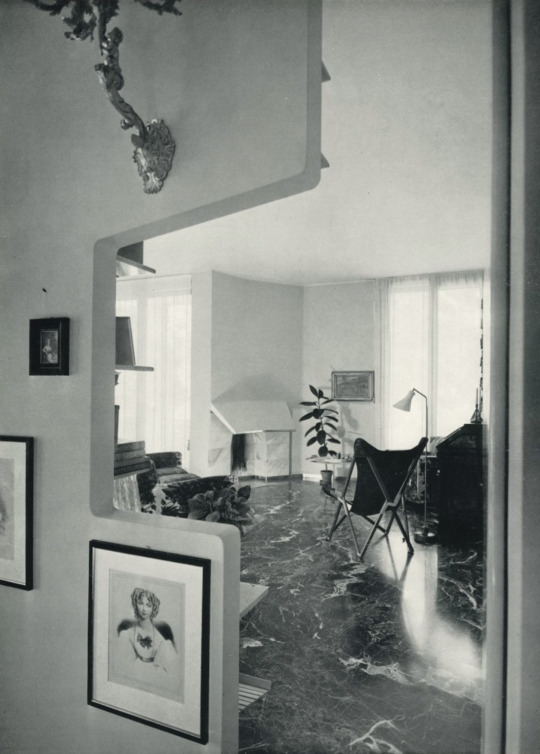

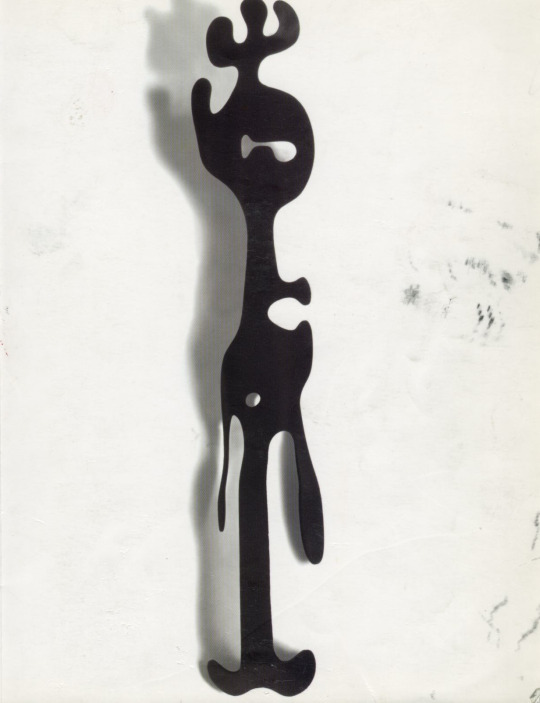

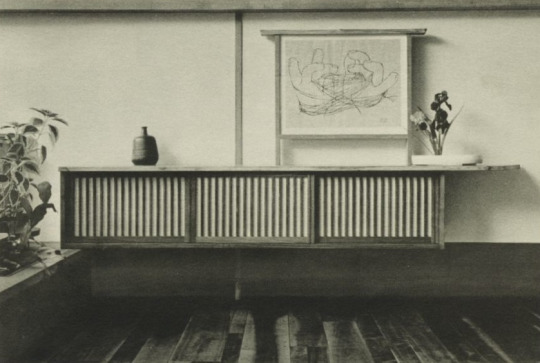

The 1962 Nakashima catalog shows the same artistry and meticulous attention to detail as his furniture. Like his tables, chairs, case pieces, and lamps, like his writing, architecture, and his business, it is suffused with his philosophy. Humility, simplicity, serenity, natural beauty, harmony, pride, dedication—all were a way of life to him. The catalog expresses his philosophy in its artful and well executed photographs and uncluttered layout, in the choice of fonts, the use of Japanese hand made wrappers, endpapers, and pages, and hand-sewn binding. It states his philosophy and his approach, succinctly, in its text.

On craftsmanship and modern design:

“In a world where fine manual skills are shunned, we believe in them, not only in the act of producing a better product, but in the sheer joy of doing or becoming. We feel that pride in craftsmanship, of doing as perfect a job as possible, of producing something of beauty even out of nature’s discards, are all homely attributes that can be reconsidered. It might even be a question of regaining one’s own soul when desire and megalomania are rampant…”

“In proportion to the flood of consumer goods, we are probably at one of the lowest ebbs of design excellence the world has seen. It requires a genuine fight to produce one well designed object of relatively permanent value.”

On the idiosyncratic nature of his output:

“Many of our pieces are one-of-a-kind and cannot be reproduced nor accurately shown. They often depend on a particular board with extraordinary characteristics. Such boards are at times studied for years before a decision is made to its use, or a cut made at any point. Distinguishing features are fine figures in graining, burls, rich and deep coloring, unusual profiles, and even areas of decomposition.”

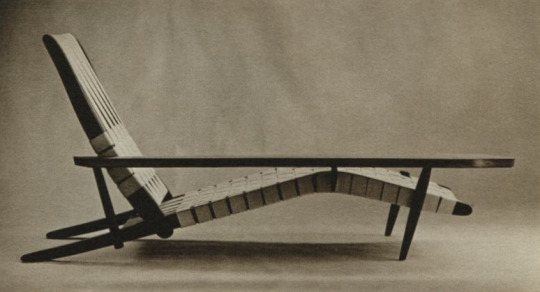

On using solid wood:

“Solid wood is a challenge. It is continually ‘alive’ and ‘moves’ depending on weather conditions, moisture content of the air, and temperature. Each board of each species is individual and must be understood; the good characteristics exploited.”

And, significantly:

“Furniture should be lived with and not considered something overly precious.”

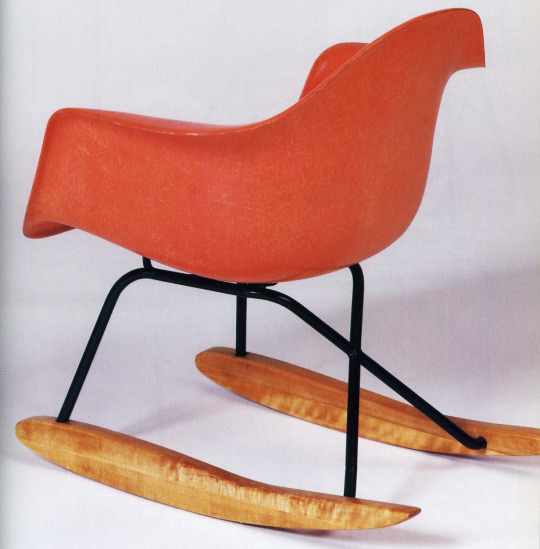

The Nakashima catalog is unlike any other I can think of. Part admonition, part jeremiad, it enjoins or challenges his customers to see things differently and to share with George his deep respect for craft traditions, nature, and the well-springs of creativity. Cost was not a formidable obstacle. The 1962 price list shows a Conoid triple chest with sliding doors selling for $360.00; a seven-foot hanging wall case with free-edge front for $350.00; a floor lamp for $105.00; a 66-inch slab coffee table for $150.00, a double pedestal desk for $225.00, and a New chair with rockers and arm for $125.00. This at a time when a Dunbar chest of similar size cost up to $1,500.00, a Herman Miller desk cost $500.00, and Eames aluminum group armchair cost $195.00. Clearly, on some level, George was at least as interested in getting his message across as turning a profit, or maybe he just enjoyed what he was doing.

The 1962 catalog shows George walking the walk as well as talking the talk; it is a document that embodies and projects what he is about, both in word and act.