Originally posted June 18, 2009 on interiordesign.net

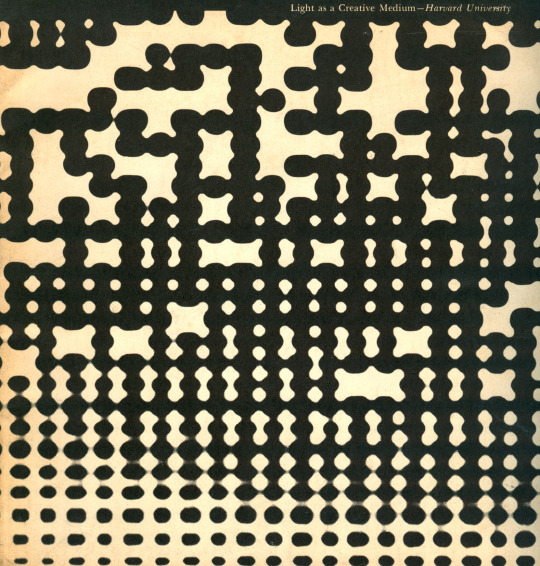

“Everything that is seen enters the human eye as a pattern of light qualities. We discern forms in space as configurations of brightness and color. The entire visible world, natural and man-made, is a light world. Its heights and depths, its majestic outlines and intimate details are mapped by light.” So stated Gyorgy Kepes in “Light as a Creative Medium.”

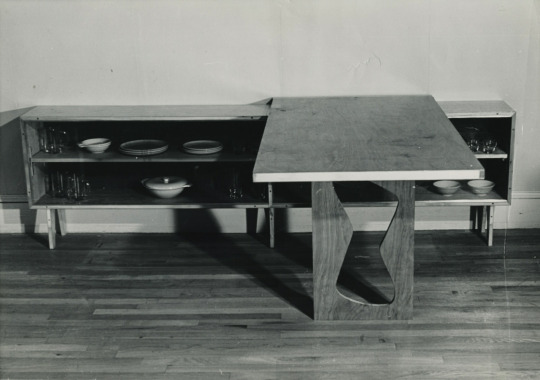

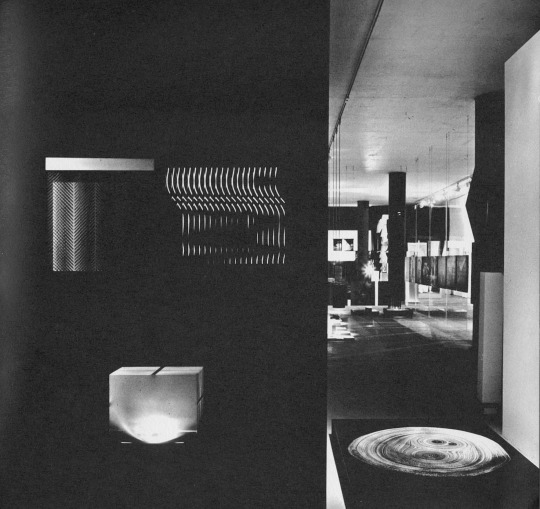

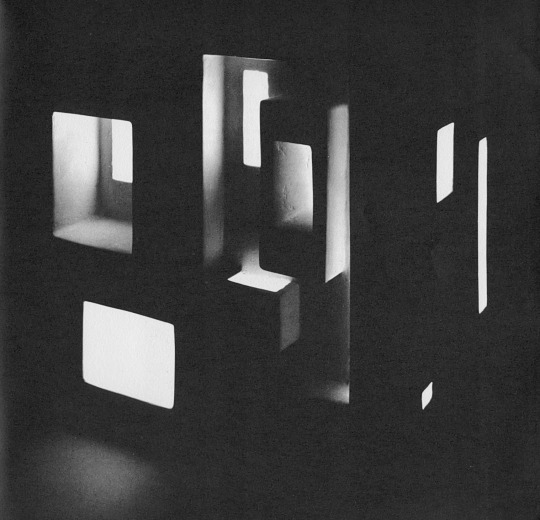

Hungarian-born painter, designer, educator, and art theorist Gyorgy Kepes (1906-2001) spent a large part of his career exploring and explaining light as a physical, cultural, and artistic phenomenon. A student of Moholy-Nagy in Europe, Kepes went on to teach a workshop on light and color at the New Bauhaus in Chicago, and later at MIT. The 1965 exhibition he planned and designed at Harvard, “Light as a Creative Medium,” is thus a summation and continuation of 40 years of work. A stated aim of the exhibition was to trace the deep and deeply historical significance of light as a central tool of art.

“There is an age-old dialogue between man and light…Our human nature is profoundly phototropic. Men obey their deepest instincts when they hold fast to light in comprehensive acts of perception and understanding through which they learn about the world, orient themselves within it, experience the joy of living, and achieve a metaphoric, symbolic grasp of life,” Kepes continues.

The original language of this dialogue was fundamentally altered by the advent of the electric light, co-incident with the rise of cultural modernism and the modern city.

“In all major cities of the world, the ebbing of the day brings a second world of light…It is the world of man-made light sources, the glittering dynamic glow of artificial illumination of the twentieth-century metropolis…Washing away the boundary between night and day has lost us our sense of connection with nature and its rhythms. If our artificial illumination is bright and ample, it is without the vitality, the wonderful ever-changing quality of natural light. For the warm, living play of firelight we have substituted the bluish, greenish television screen with its deadening stream of inane images…”

This, of course, was a source of frustration to Kepes. Despite a quarter century of cultural preparation, modern artists still had not grasped the centrality or potential of light as a medium of art. As Kepes put it, artists were “afraid of light, the use of light, and the meaning of light.” This “spectrum of despair” corresponded with other perceived failures of the modernism project that were hashed out in the mid-1960’s, particularly in regard to the urban milieu. Against this backdrop of criticism and doubt, Kepes presented a call-to-arms to artists, designers, and architects, and offered a message of hope for the future: “This exhibition is a plea…for an emerging environmental art: the creative management of light…It is an art of enormous promise. For painters, sculptors, and makers of motion pictures, a field for creative originality…For architects and planners, a mighty tool with which to reshape our tangled, cluttered cityscapes. For the ordinary citizens of our dizzily expanding urbanized world, an aid to orientation in their surroundings.”

Author’s note: In 1964, at the same time that “Light as a Creative Medium” was being organized, a young artist mounted two exhibitions in New York City galleries. Dan Flavin’s first exhibition in fluorescent light, at the Green Gallery, addressed Kepes’ plea for a “radiant new visual poetry” and marked a watershed in the advent of 1960’s minimalist art. In the context of the Harvard exhibition, it is interesting that the minimalist movement was directly influenced by this use of light and color.

Images 1-4 from the catalog “Light as a Creative Medium” published by Harvard University in 1965; image 5 by Bernice Abbott in “Language of Vision” by Gyorgy Kepes; image 6 by Billy Jim, courtesy of Stephen Flavin; image 7 courtesy estate of Dan Flavin.