Originally posted March 5, 2009 on interiordesign.net

Christopher

Dresser (1834-1904) cut a wide swath across 19th-century culture and

commerce. In a career spanning 50 years, he wrote and lectured about

botany and ornament, and produced an array of designs in areas as diverse as

furniture, dinnerware, glass, ceramics, silver, textiles, and

wallpaper. Hugely successful and influential in his day, he was

nonetheless marginalized after his death by a design press that all but

lionized William Morris.

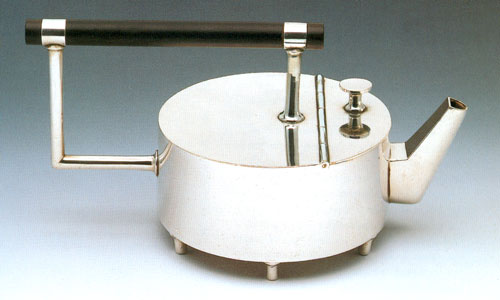

Reassessment was slow to take place, and focused on the proto-modernist aspects of his work, specifically on the geometric and austere silver designs of the 1870’s and 1880’s. Nicholas Pevsner devoted all of one paragraph to Dresser in his 1936 Pioneers of the Modern Movement, citing a pair of silver cruets for their startling simplicity of form. Herwin Schaefer similarly mentioned Dresser in passing in Nineteeth Century Modern (1970), again focusing solely on the prescient modernity of the silver designs for Hukin & Heath and Dixon & Sons. Only in the past twenty years has a fuller and more balanced picture of Dresser emerged. Notable here are the monographs by Widar Halen (1990) and Stuart Durant (1993), and the 2004 exhibition catalog Shock of the Old: Christopher Dresser’s Design Revolution. These accounts have in common an attempt to illustrate the range of Dresser’s work, and to relocate Dresser as a Victorian thinker and creator, as much a man of his day as ahead of it.

Still, in all these writings the astonishing silver designs take center stage. Executed after his epochal trip to Japan in 1877, the silver and silver-plated teapots, decanters, tureens, and toast racks look to our eyes more like Bauhaus or post-modern objects than like Victorian things. They represent a body of work unrivaled in the 19th century, and still relevant in the 21st century—original examples can fetch in excess of $100,000, and Alessi recently re-issued a series of Dresser’s silver designs in stainless steel. Lost amidst the fanfare for the silver design is Dresser’s work in tin, copper, and brass.

Generally, the designs in these humble metals are treated as poor cousins to the silver designs, and they garner less print and fewer illustrations in the literature. To some extent, this is because less is known about this work, including which designs Dresser himself was responsible for. Still, there is no doubt that in the 1870’s and 80’s Dresser’s office did work in copper and brass for Benham & Froud, and in tin, copper, and brass for Perry & Sons of Wolverhampton. The latter company in particular has attracted my attention, and I have over the years examined 20-25 different Perry & Sons designs that I would attribute to Dresser, and I would guess there are at least as many more still out there. I have collected about a dozen examples, six of which are illustrated here.

What unites and identifies Dresser’s

work for Perry & Sons is what separates it from most Victorian design—the

interplay of geometric forms, the origami-like foldings, the bold use of color,

and the lack of superficial ornament. The low cost of the materials,

combined with the relative ease of working them, allowed a tangible freedom of

expression not present in the silver work. The tin (and brass) candle

holders and watering cans convey a sense of delight and exuberance; they are

inexpensive but confident works that make a bold and progressive visual statement.

I would suggest that the Dresser design team’s tin pieces for Perry were to the

late 19th century what the Nelson design team’s clocks for Howard Miller were to the 1950’s—the output of a laboratory

for creative experiment and design-play, and a proving ground for new shapes

and forms. Yet, before we rip Dresser out of his Victorian milieu, we should

point out, as one wag did, that while Dresser was designing forward-looking tin

candle holders, Edison was inventing light bulbs.