Originally posted May 27, 2010 on interiordesign.net

Thanks to an invitation from interior designer and friend, Brad Ford, who procured tickets for a group of people including Joan and Jayne Michaels, I was able to tour Philip Johnson’s Glass House last week, my first pilgrimage to a modernist icon outside of New York.

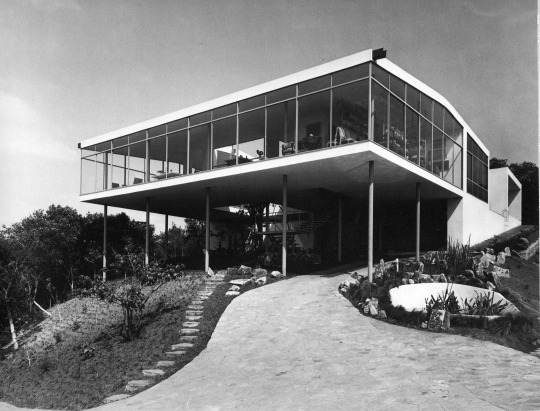

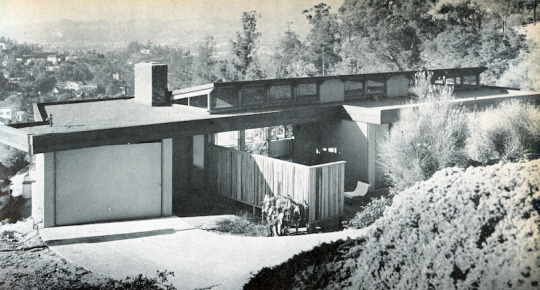

The White Gods (Tom Wolfe’s term for Gropius, Breuer, Mies, et al) were smiling on us—the day was warm and overcast, with enough sunlight for reflections and shadows. I entered the 47-acre property in New Caanan with an open mind, ready to be enchanted by the combination of natural and man-made beauty, and in this I was not disappointed. The story is that Johnson purchased the initial parcel five minutes after he saw it, because of the promontory overlooking the woods and the pond. Built atop this promontory in 1949, the Glass House took the idea of a glass box, where the view became the walls, to an extreme: farther than the Eames house, which had about half glass and half multicolor panels in its cladding, and as far as Mies’ Farnsworth House, built in 1951 but designed in 1945.

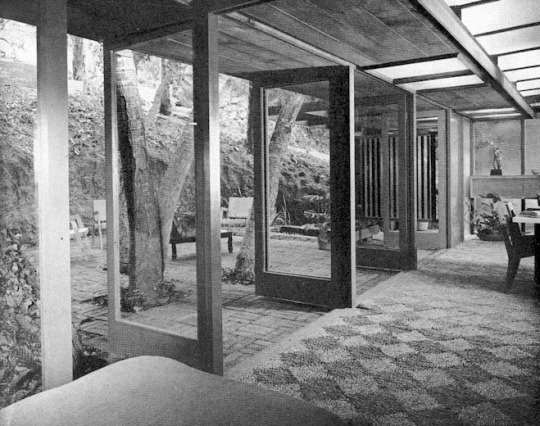

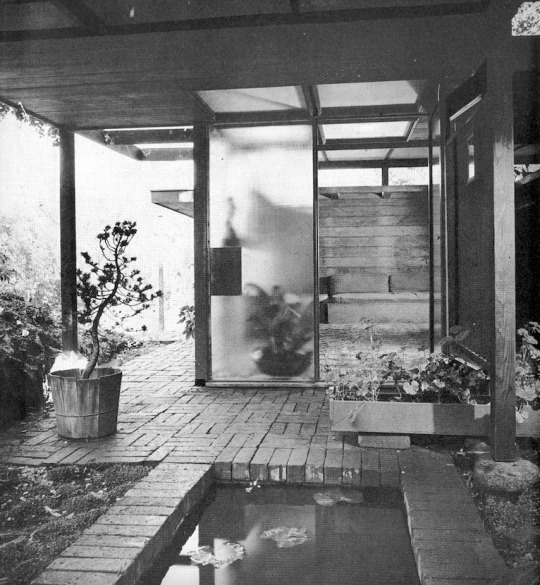

Walking around the Glass House, and the Brick House opposite it, the dynamic and avante garde elements are apparent: with its charcoal-painted steel I-beams and glass walls, the house disappears into the landscape as much as a house can. The relationship between inside and outside is fluid, influenced by lighting conditions and where you are standing. From outside especially, ever-changing reflections of trees make the view layered and complex. In some respects, this was something new and daring, and to the Beaux-Arts establishment, vaguely threatening.

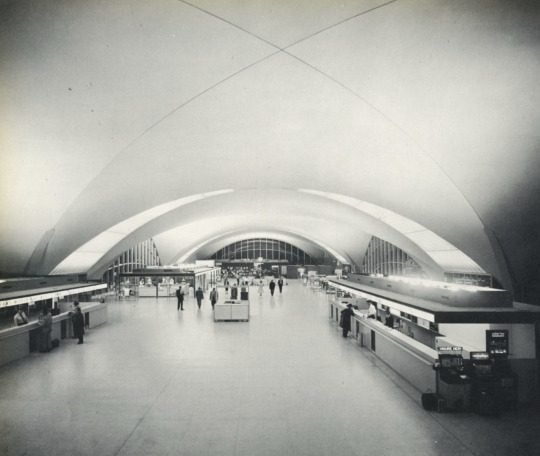

Yet, the overweening impression at the estate is of classicism, or neo-classicism, and the direct representation or allusion to classical architecture. This is not a new observation, and Johnson’s Wikipedia entry points to his classical scholarship at Harvard, and to his two grand tours of Europe. Surely, the stripped-down modernism of the Glass House and Brick House is more Doric than Corinthian, with the vertical steel I-beams and the row of tall trees behind the house referencing colonnades. Also, the triangular paths between the house and the guest house govern the sight lines along 45-degree angles, a Greek practice. In more overt ways, the underground structure housing the painting collection has a façade based on Agamemnon’s tomb on Mycenae, and the building housing the sculpture collection is a postmodern archaeological essay.

What all this means, I don’t know, and when Johnson was alive, it didn’t matter much, as it was after all a private residence. On one level, the Johnson estate makes a statement about the intimate connection between classicism and avant-garde modernism, a connection refuted for a time at least by most practicing modernists.

In Johnson’s life, the abiding relevance of history is tantamount, and this makes it harder to forget Johnson’s more than brief flirtation with Nazism prior to WWII. Given Johnson’s youthful fascistic tendencies, and given his bequest of the estate to the National Trust, what were private issues have become public matters. Did Johnson see himself as a citizen of the world or as emperor of his own domain? Was he referencing Greece of the Agora or Rome of Caesar’s Palace? Was he aware that Agamemnon has been portrayed as stubborn and arrogant? That he left the estate to the common weal is a good sign; what exactly the estate signifies speaks to whether the bequest was an act of altruism or an inside joke.