Originally posted June 3, 2010 on interiordesign.net

I got around to perusing a design book this week that was on my summer reading list. Published in 2003, it’s called “Where’s My Space Age,” by Sean Topham. Subtitled “The Rise and Fall of Futuristic Design,” it traces the roots of the Space Age to WWII rocketry (Werner von Braun et al) and Cold War technological competition, though after a chapter on space flight it brings the disquisition down to earth with a long section on the impact of space-mania on 1960’s living environments.

Rather than a book review, this is a book reaction, and that reaction is visceral. Topham sets the stage for his book with a comment from a 12-year-old boy on the eve of the lunar landing in 1969. I was ten at that moment, and so was a child when manned space flight went from dream to reality. Part of Topham’s argument has to do with a child’s sense of wonderment representing a broader cultural reaction to the exploration of space-he suggests the idea of a fresh start several times, and notes that space travel entered the home first in the form of children’s toys.

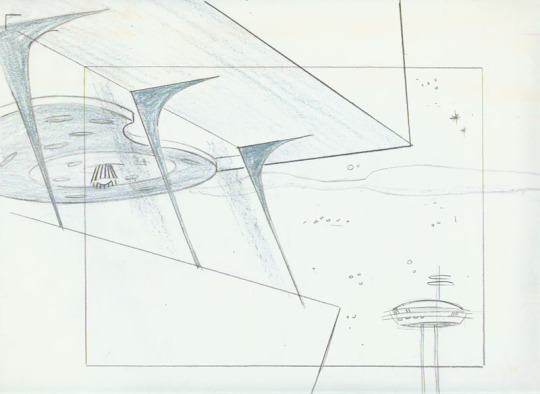

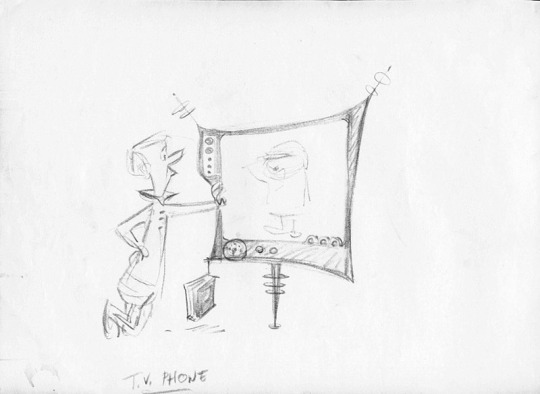

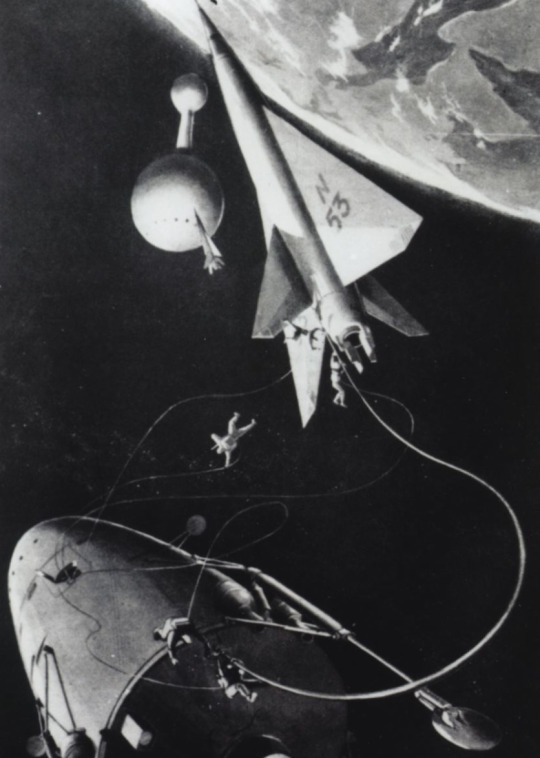

It is hard for someone my age to look back at the imagery of the early postwar space age without a tinge of nostalgia, but look back we must because Topham argues, rightly, how important visual information was in disseminating ideas about space travel. From Arthur Clarke’s 1951 “The Exploration of Space” on, a succession of images prepared people for the coming conquest of space. Confidence, swagger, and technical mastery were suggested graphically, and awe was elicited with photos of rocket launches and breathtaking views from space. Shown here is a rendering from Clarke’s factual rather than fictional account, and a shot of the jammed nose cone on Gemini 9.

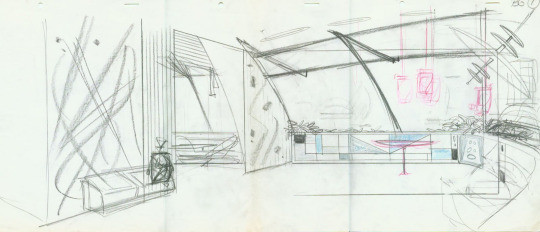

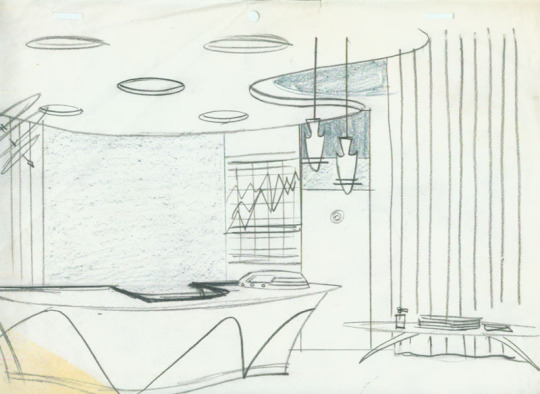

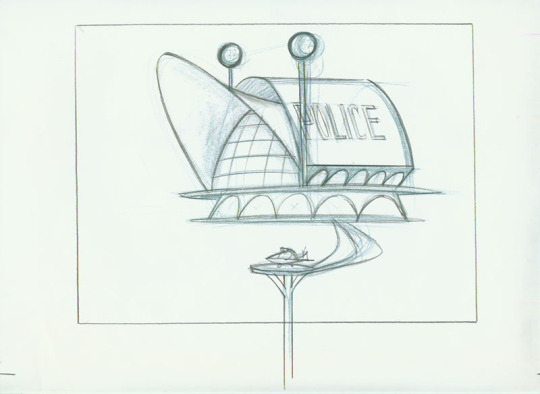

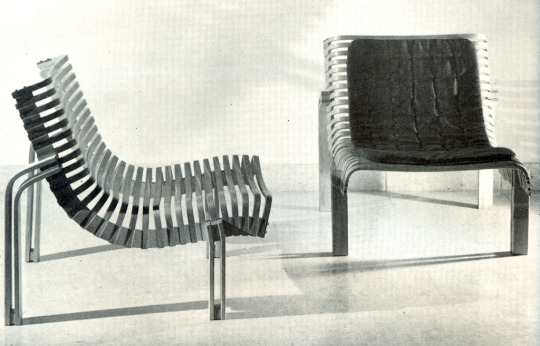

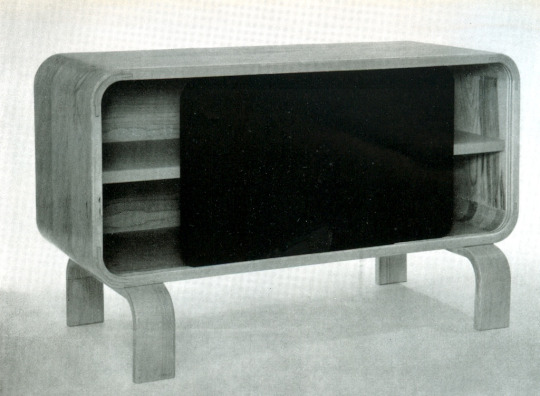

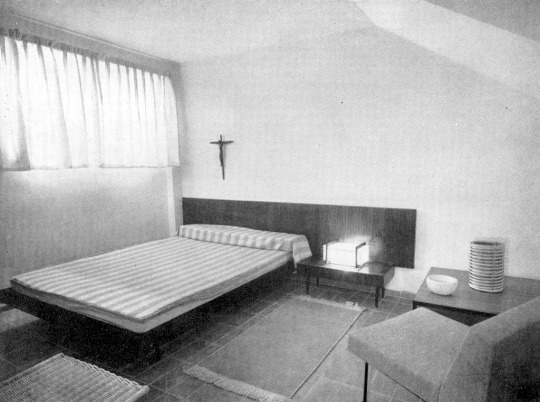

This visual component was brought home, literally, by architects and designers during the 1960’s. For Topham, the futuristic “look” of the 60’s was deeply influenced by themes and imagery drawn from space, more directly in references to space helmets, space suits, satellites, and capsules, less directly in the use of aluminum–the material of early satellites–and perhaps the vivid blues of shots of earth from space. Moreover, space helped usher in an era characterized by disposability–multi-million dollar rockets were discarded after one use, as were paper dresses, while plastic chairs and tables would be replaced rather than repaired.

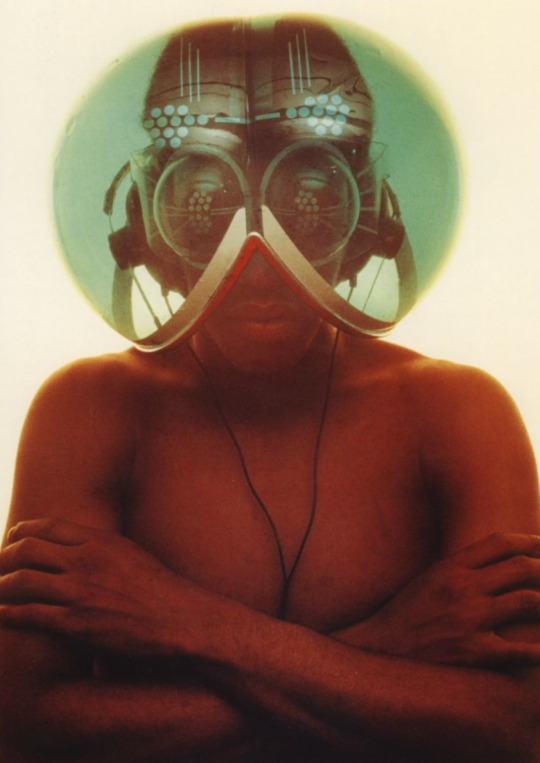

Topham illustrates a wide array of futuristic 60’s design, including Haus-Rucker-Co’s “Fly Head” (1968), shown here, but the essence of it, for him, can be distilled into Matti Suuronen’s ellipsoid Futuro House of 1968, and the furniture designs and interior landscapes of Verner Panton. Topham points out that the flying-saucer shaped Futuro House, shown here, which represents the concept of pod living, was designed as a transportable ski cabin. Panton’s Visiona 2–depicted here–captured the exuberantly colorful and youthfully irrepressible (and irresponsible) character of space age design, while shifting styling from the clean lines inspired by spacecraft interiors to a more organic terrain–more “Barbarella” than “2001.”

Ultimately, according to Topham, the era of space age design was undone by its own excesses and by the oil embargo and recession of the early 1970’s–the cost of plastics rose with the price of oil, and a scenario of resource scarcity trumped the scenario of disposability. Curiously, Topham fails to bridge the idea of pod living into the era of sustainability. Surely, some notion of living in a compressed space, analogous to a spaceship or space capsule, remains relevant at a time when our greatest drain on resources comes from our egregiously outsized residences.

Ironically, the smallest prefab dwelling at a recent MoMA exhibition was intended as a ski cabin–40 years later, an idea of pod living still has to be couched in recreational terms.