Originally posted September 2, 2010 on interiordesign.net

Clive Carney was an Australian interior designer who took a hiatus in the late 1950’s to assemble materials for a book describing and depicting best-practice modernist interior decoration in a global context. His “self-imposed assignment” took him to places such as Paris, Helsinki, Stockholm, Mexico City, and New York. A considerable amount of time was apparently spent in Los Angeles, Palm Springs, Honolulu, and Miami. Evidently, no hardship was spared in the search for décor. Between daquiris and dips, he managed to shoot or cull photos of interiors by a who’s who of designers and architects, in a range of styles from austere to opulent, and accessible to elite.

Among the luminaries sampled are Robsjohn-Gibbings, Gropius, Breuer, Wormley, Kagan, Dorothy Draper, J. Leleu, Kenzo Tange, Laszlo, Arbus, Knoll, Topiavaara, Gardella, and Fornasetti. Projects range from private residences to offices, restaurants, and hotels. Carney’s book, “International Interiors and Design,” published in 1959, is organized into ten chapters, with lead essays by the likes of Paul Reilly (“The State of British Design Today”), Edward Wormley (“Modern Design”), Jules Leleu (“Decorative Art in France”), and Carl Malmsten (“To Build and Dwell”). There are several dozen eye-popping interiors, so selecting six to illustrate here is a subjective task. What I’ve come up with follows:

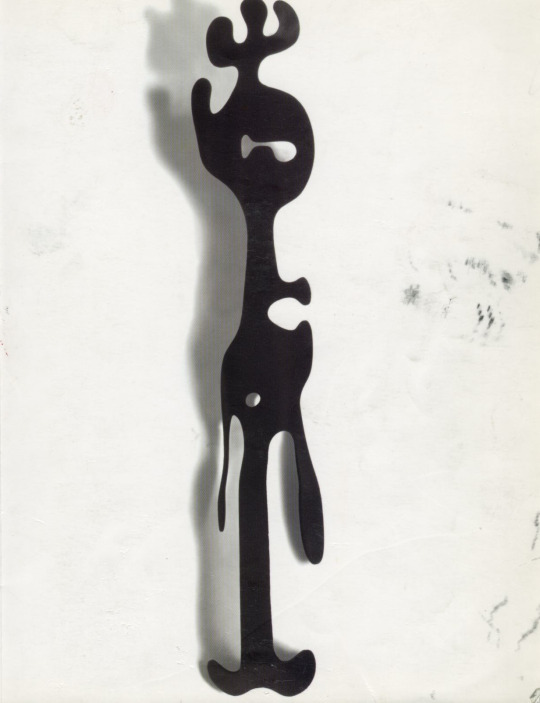

1. Stairway in the home of Walter Gropius, Lincoln, Massachusetts. Gropius and Breuer, architects. Nice photo by Robert Damora. Note the guy with the martinis. I’m guessing Carney was schmoozing his way around the world. Very Mad Men. I don’t know who did the wall sculpture–Arp, Sidney Geist?

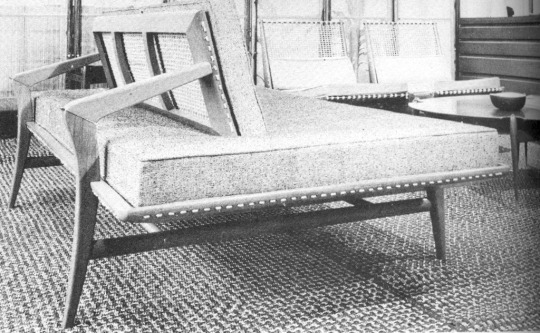

2. Living room of a Los Angeles residence. Cannell and Chaffin, designers. A relatively humble project, but it has clean lines and a hospitable, serene feel. I like the window treatment and the arrangement of the furniture in relation to the fireplace.

3. Living room in Milan. Interior design by Piero Fornasetti. Fabulous and fabulist. Could anyone integrate pattern, or relate objects to graphics, better than Fornasetti?

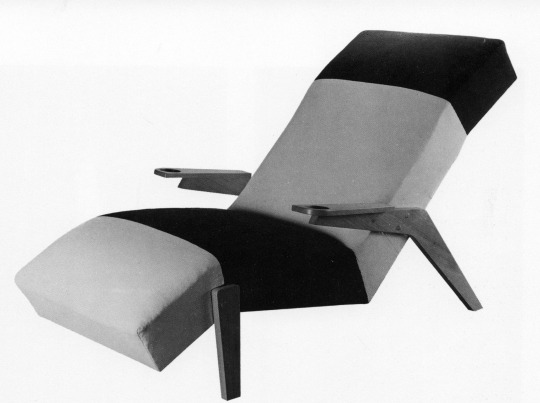

4. Living room in a New York apartment. Interior by Vladimir Kagan. Kagan’s work as an interior designer is less-known than his furniture design, but like Wormley, Robsjohn-Gibbings, and Laszlo, Kagan did commission work–and interiors–for clients. The faux wall and the dramatic built-in counter give the space an almost surreal feel.

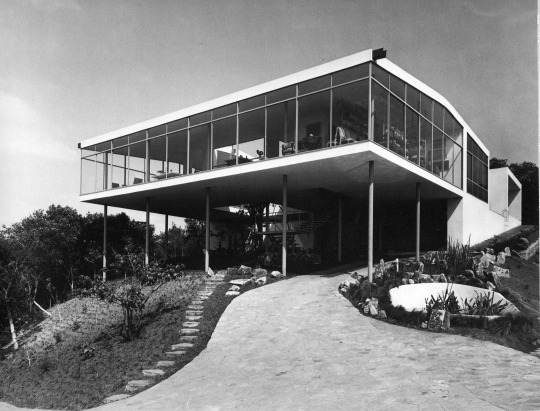

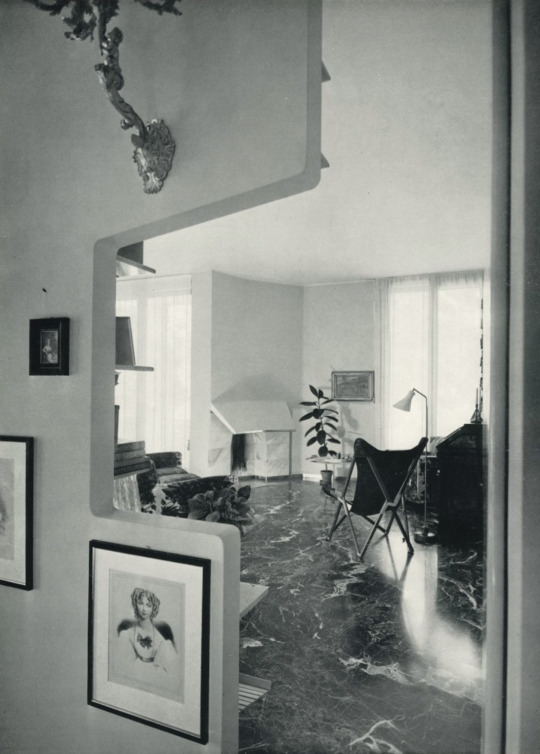

5. Living room in the architect’s house in Milan. Ignazio Gardella, architect. The photo, taken by Carney, shows a vista bounded by a cut-out wall. The black marble floor and white walls, which could read cold, are warmed up by the wood furniture (which includes bookshelves just visible on the inside of the cutout), the gilt candelabra, and the artfully arranged artworks. The sheer drapes provide a soft illumination. Very sophisticated.

6. Interior by Andre Arbus. Speaking of sophisticated–I don’t know where this room rates in Arbus’ oeuvre, but it looks like a paradigm statement for understated elegance to me. Note the sculptured stone table base vis-à-vis the frieze, the full use of the height of the room, and the reflective surfaces of the mural and cupboard. Note, also, the martini glasses on the table–another soiree for our peripatetic author?