Originally posted November 24, 2010 on interiordesign.net

Beginning with de Stijl, geometry became an obvious metaphor for the scientific and mechanistic modes of thinking associated with avant-garde modernism. Mondrian’s canvases, arguably influenced themselves by Frank Lloyd Wright’s Prairie School architecture, became templates for mid-century wall systems and modular case good systems, as well as graphic inspiration for architecture.

All of these applications self-evidently involved rectilinearity or at least linearity–the so-called deconstruction and reconstruction of the box, applied both to surface and volume. Famously, this was the approach taken with Rietveld’s Red and Blue chair, which was explicitly linear, a rigid composition of wooden planks designed with little regard for comfort. Much cantilevered, Bauhaus-inspired furniture would also fit into this camp, though with somewhat greater interest in comfort. In the opposing, organic camp, are chairs such as the Womb chair, ergonomic in character, curvilinear, and fitted to the human form.

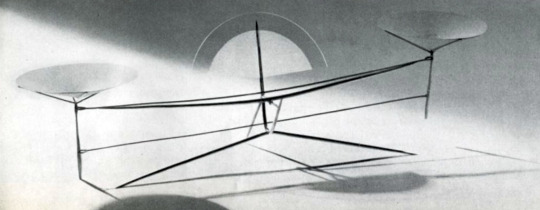

The circle occupies a place somewhere in between though much closer to the geometric camp; in Platonic terms, the circle is perfect, the ultimate geometric symbol of wholeness, unity, infinity. With tables, there is a long tradition of circular design: the Knights of the Round Table, round table discussions, etc. (note the underlying egalitarian aspect of this shape–no one sits in a privileged position).

Though curvilinear, the circle does not suggest itself for chair design–people have curves but are not hemispheric or conical, at least generally speaking. A circular or spherical chair is not inherently ergonomic, though it can be rendered comfortable with slings, padding, pillows, or butt-shaped indentations. Partly for this reason, and likely for technical reasons also, relatively few chair designs hewed to the geometry of the circle. And those that did tended to have an agenda: either experiments in form or ideological or symbolic statements of some type.

Beginning in the early 1950’s, the circle was deployed in chair design in the work of Donald Knorr, Lina Bo Bardi, and Roberto Mango. Knorr’s chair, shaped from a ribbon of sheet metal, shared first prize in a 1950 MoMA Low-Cost Furniture competition. Distributed by Knoll, and painted red, yellow, or black, with black metal legs, the chair possessed a minimalist and elegant beauty. Intended to be comfortable, the chair was also offered in a padded version, just in case. Bo Bardi, the Italian/Brazilian architect and designer, contributed an eye-catching chair consisting of a hemispheric seat floating inside a round tubular metal base. The chair could be used parallel to the ground or at an angle, for a variety of seating or lounging positions. The image here, which uncropped shows two such options, is from the cover of an Interiors magazine from the early 1950’s. It is notable, and surely meaningful, that Bo Bardi is a woman designer and the circle is a female archetype. Unlike Knorr and Bo Bardi, the Mango chair illustrated here is made of wood–in this case shaped plywood–and it looks like a James Prestini bowl on legs. This chair is part of a series done by Mango in wood and metal, exploring the possibilities of the circle as a chair frame. Significantly, all the designs referred to here had one thing in common: a lack of commercial success, and hence a small production run.

Continuing this tradition were three circular chair designs from the late 1960’s. In the case of Arman’s 1969 chair for Atelier A, consisting of two steel rings with a leather sling, the intent was not serial production but design/art; more a functional sculpture than a seating solution. Joe Colombo’s 1969 Tube chair for Flexform cleverly used round tubes looking like paint rollers to achieve a variety of seating options. Despite advertisements pointing to the comfort obtainable through the flexibility of assembly, the chair was far too radical for prevalent taste cultures.

Somewhat more accessible, and commercially viable, was the work in plastic by Finnish designer Eero Aarnio. His Pastille chair of 1967, with its contoured seating indentation, took the circle in an ergonomic direction, while his Ball chair of 1969, shown here and based on a sphere, required cushions and pillows to suggest comfort. The Ball chair stood, and stands, as a production analog to the utopian 1960’s preoccupation with self-contained living environments.

While this is not an exhaustive list of post-war circular chair designs, the two clusters around 1950 and 1969 do suggest an underlying cultural rationale at those moments—some metaphoric or symbolic reason for this attraction to the circle. A topic I will deal with when I get around to it…